Art always has two balancing demands: technique and aesthetics. Sewing requires that we understand the basics of construction, how to operate a sewing machine, how to handle fabrics and shears to get a good cut–but it also requires that we have a vision, a story to tell, a voice that we want heard.

That second part has always been the bigger challenge to me. I lean toward detail-orientedness, so drilling down on the technique side of sewing was immensely appealing to me. I loved the idea that I could master hand-eye-coordination s𝓀𝒾𝓁𝓁s using soft goods, loved how that was a challenge with immediate rewards. I struggled more with the idea of developing a VOICE, of using the product of my process to tell a story that was consistent and cohesive and cogent.

I think it’s an ongoing, meandering path, to be honest–I want to put that out right at the beginning here. I’m not saying people who don’t know what they’re searching to say shouldn’t sew, that’s crazy: the sewing is WHERE we learn what we want to say, oftentimes. You don’t have to know it at the beginning, it can be a thing that’s hard to pinpoint up close but becomes very clear with enough distance, when viewing the gestalt.

Ola Hudson embodies this idea to me. As a designer, she is not at all a household name, but you’ve one hundred percent seen her work, and her vision has indelibly impacted the world of fashion and design in ways that I think were subtle but pervasive. She has a clear aesthetic that stands out and has influenced designers who came after her.

Ola Hudson started her professional life as a trained dancer, and history seems to indicate she was talented and had a bright future in the field of dance. She met and married a graphic designer who did magazine work, and early in their marriage did some modeling that introduced her to the world of fashion.

From there, Hudson seems to have been a quick study, and moved into designing women’s wear for trendy boutiques, first in London and then in Los Angeles. She was particularly successful in creating avant garde looks for rock-and-roll, and you might not know it, but some of the LOOKS you’ve loved for decades were her inspired idea.

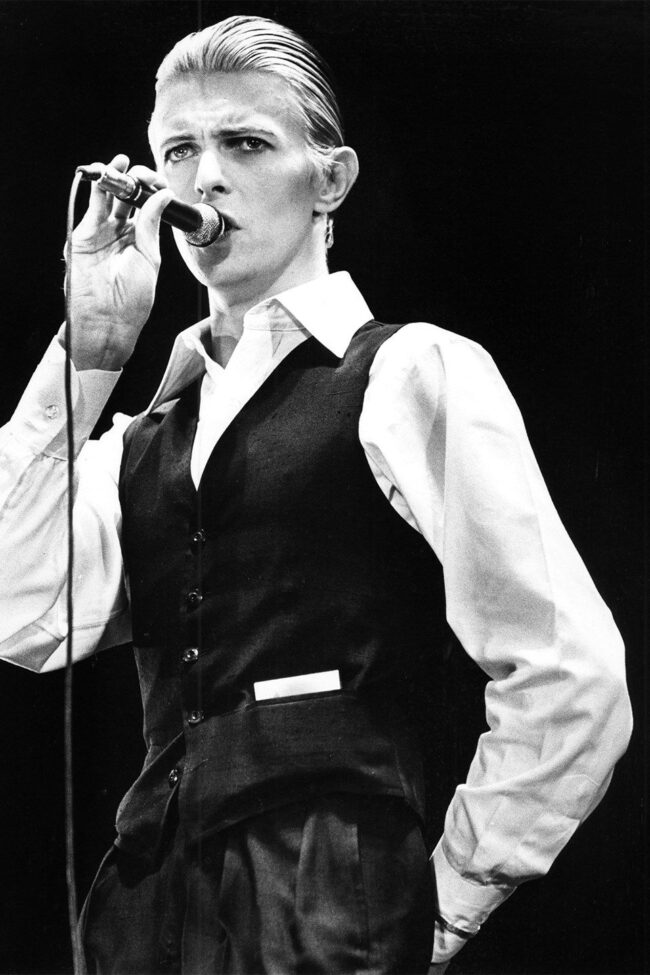

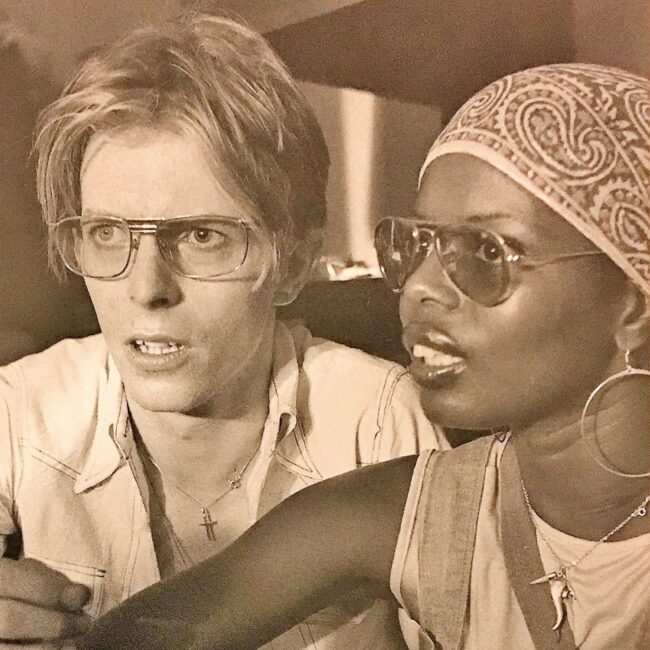

David Bowie’s infamous vested suit? Ola Hudson design.

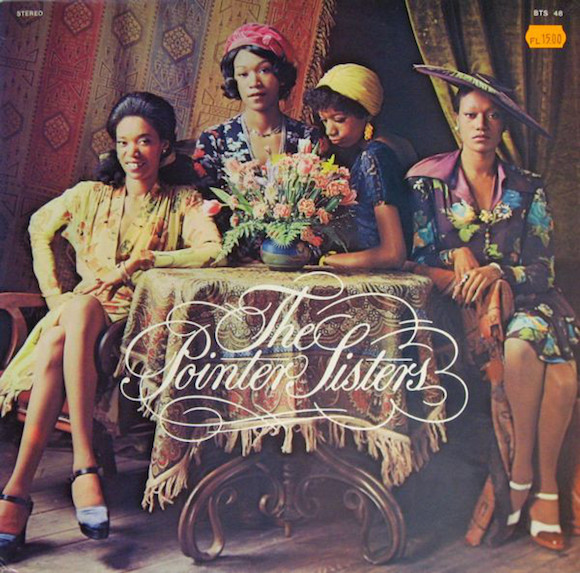

The cover of this Pointer Sisters album? Ola Hudson dresses.

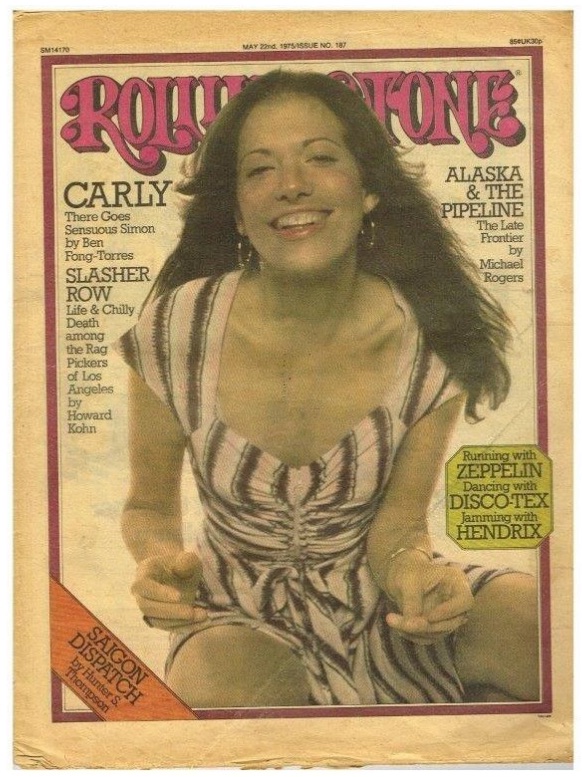

Carly Simon on the cover of Rolling Stone? Hand-sewn dress by Ola Hudson.

John Lennon. Ringo Starr. Diana Ross. Janet Jackson. Dancer Linda Gold. Costume designs for the film The Man Who Fell To Earth. Fashion lines for Henri Bendel and Nieman Marcus department stores. Her designs filled a boutique called Skitzo along Los Angeles’ Sunset Strip.

Her work seems to have universally drawn on street wear of the day, but in a tailored, elevated way that reflects a very specific world view. She is quoted as saying, “[Design]’s getting right down to basics,” and the looks she created seem to bridge the times in which she was living with more deliberate styles from the forties.

I think it’s relevant that Hudson came to both dance and design in the sixties and seventies as a Black woman, when both those worlds were overwhelmingly white- and male-dominated. The way she worked with David Bowie specifically stands out to me: she mastered the concept of “menswear” but somehow also embraced Bowie’s gender fluidity–all while bringing in a flair for the funk and blues that thread their way through Bowie’s music. She turned his SOUND into his LOOK as he morphed between two very different personas in his career, and it’s hard for me to imagine someone who came from a background where she had never been asked to code switch making the same impact on Bowie’s transition from glam rock to monochrome and sleek.

I wonder if her experience as a Black woman in the seventies informed her ability to understand the ways in which identity can be navigated, nuanced and dual; I can’t imagine that it didn’t, and profoundly. As a white woman, I lack the experience, 𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐧 from necessity, of moving between worlds in that way; I want to work to recognize the times when that has made me complacent, not only socially (which is certainly has) but creatively, where my privilege has allowed me to avoid challenging visual concepts and shapes–and the messages they carry–because I was never asked to think in the new ways that could have questioned those concepts in the first place.

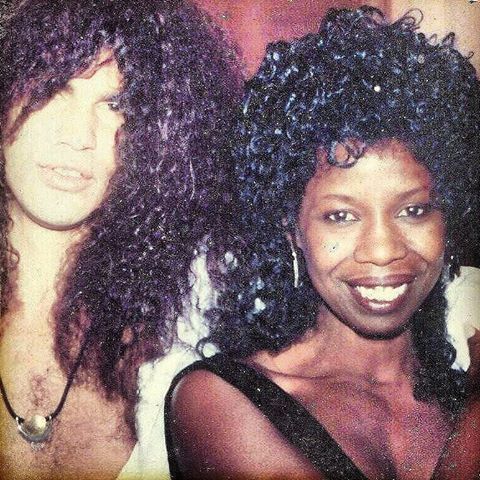

The other thing that stands out to me over and over in reading about Ola Hudson is that she’s referred to, almost without exception, as “Slash’s mom,” in reference to her older son, guitarist for Guns N’ Roses (SHOUT OUT to Eighth Grade Me, who played Appetite For Destruction until the cassette ribbon wore through). Aside from the obvious oversight that this talented, prolific, and influential designer is known more for her son’s art work than her own, I wonder if a Black woman raising biracial 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren had a unique perspective on the stories we tell by the clothes we wear?

She absolutely passed down ideas about messaging to Slash, who added a second-hand belt to a top hat before a gig in LA and made an entire persona for himself that has yet to fade–did she communicate to him growing up how simply but powerfully the things we wear can tell others about who we are? Can pass along a cohesive narrative about the kind of people we want to be? About what we most value and what we think of ourselves? Or even that we can build ourselves a safe place to hold space in front of an audience whose intentions toward us are unclear?

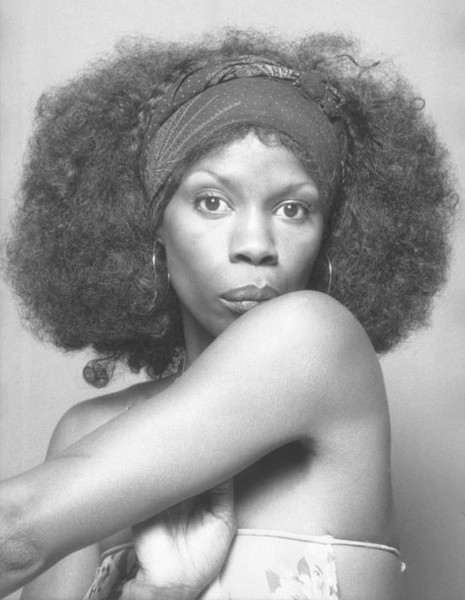

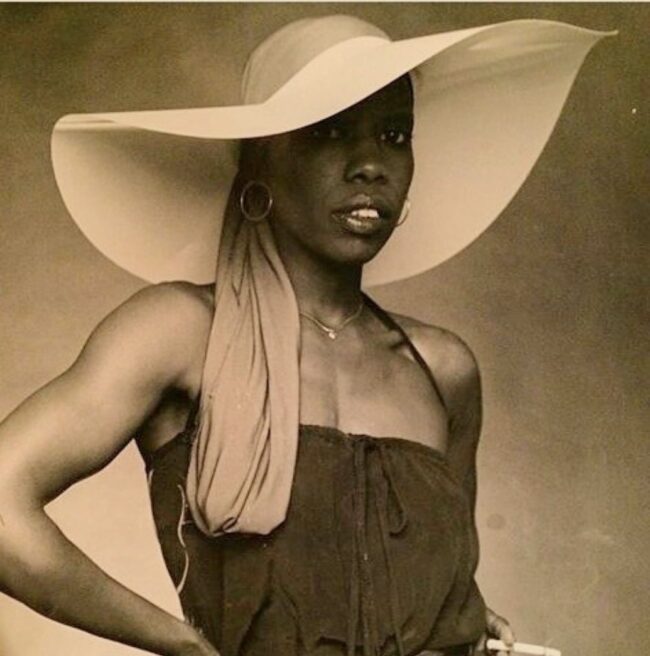

Hudson was known for her flowing retro-inspired dresses, her natural curls, and her striking facial features. She is universally remembered by those who knew her in life as a woman with strong ideas.

Ola Hudson may not be a household name (although she should be), but she has influenced me and you more than we are aware–and she has lessons to teach me about translating a story into something we wear, in ways that reflect identity without apology.

Ola Hudson is a Great Woman of Sewing.